Oceans cover over 70% of our planet, teeming with life from microscopic plankton to some of the largest Cetacea ever to exist. Yet beneath the waves, our seas are under immense pressure, and one of the biggest threats they face today is overfishing.

For many of us, fish appears neatly wrapped in plastic or served on a plate, far removed from coral reefs, boats and the open ocean. We rarely stop to consider how it got there. But the reality behind our seafood is far more complex and increasingly troubling. Overfishing is quietly reshaping marine ecosystems across the globe, and unless we start paying attention, the consequences will be felt far beyond the coastline.

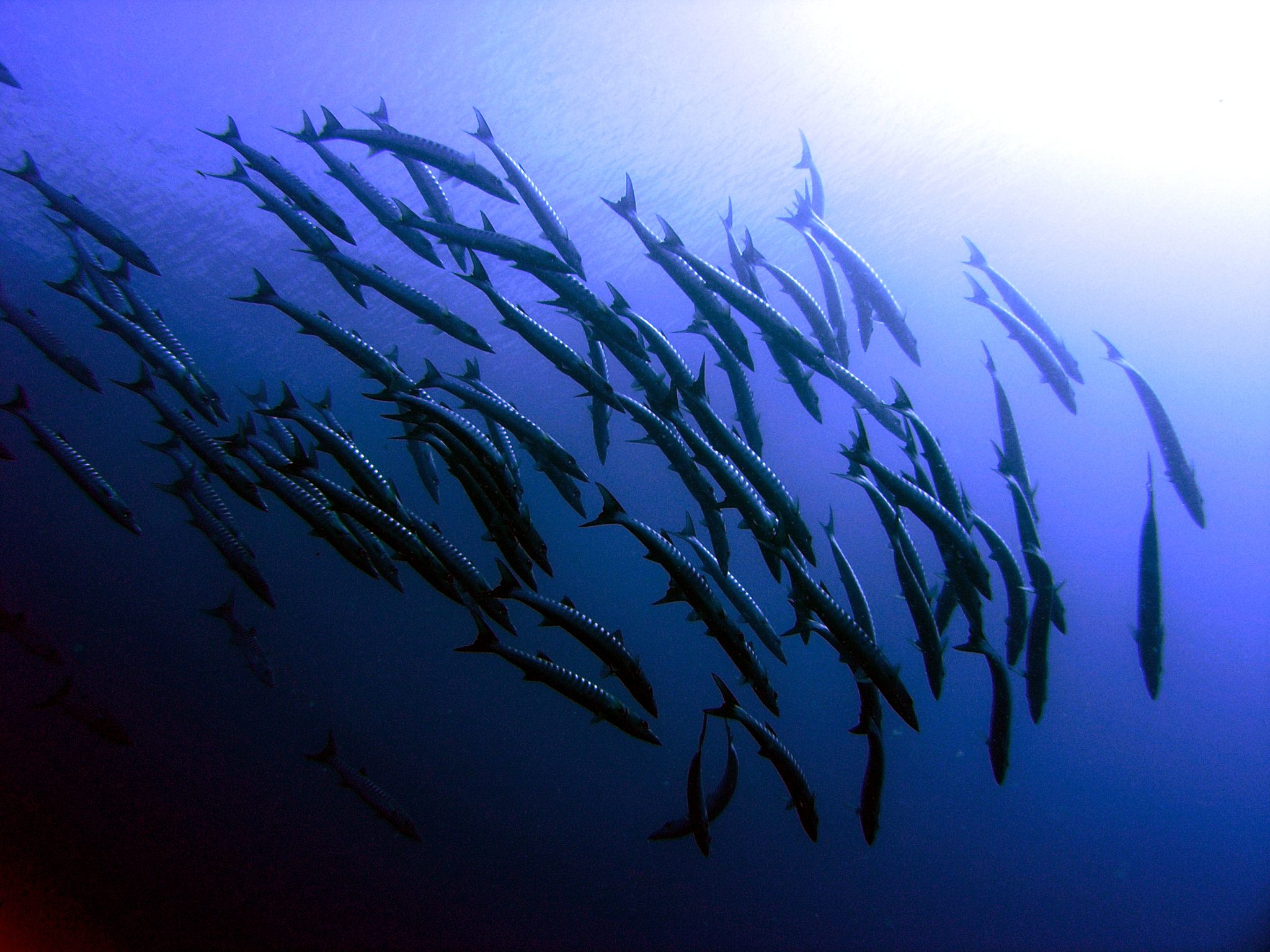

Photo by Dave Smith

So what is overfishing?

Overfishing occurs when fish and other marine species are harvested faster than they can reproduce. It is not simply about catching fish, it is about catching too many. Removing key adult individuals before they can reproduce depletes populations over time and pushes entire ecosystems out of balance, altering biodiversity in heavily fished areas.

Advances in fishing technology, combined with global demand and large-scale industrial fleets, mean we are now extracting life from the ocean at an unprecedented rate. Today, over a third of the world’s assessed fish stocks are considered overfished, and this figure continues to rise year after year.

Why does it matter?

What makes overfishing particularly dangerous is how deeply interconnected marine ecosystems are. When too many fish are removed from one level of the food chain, the impacts ripple outward. On coral reefs, for example, overfishing herbivorous fish allows algae to grow unchecked, smothering corals and weakening entire reef systems. Once these ecosystems begin to unravel, recovery can take decades, if it happens at all.

The decline of key species such as tuna, cod and reef fish has already been documented across the globe as industrial fishing becomes increasingly efficient. As populations collapse, ecosystems lose their resilience and biodiversity declines.

The consequences extend well beyond the ocean itself. Millions of people rely on healthy fish stocks for food and income, particularly in coastal communities. When fisheries fail, these communities are often the first to feel the effects, facing food insecurity and economic instability.

Overfishing also brings with it the issue of bycatch. Non target species such as turtles, sharks, seabirds and rays are frequently caught and killed unintentionally. Destructive fishing practices, including bottom trawling, further damage fragile seafloor habitats, compounding the problem.

Photo by James Matthews

Overfishing, climate and the role of research

Despite the scale of the issue, overfishing is not an unsolvable problem. One of the most powerful tools we have is data. Understanding what lives in our oceans, how populations are changing and where pressures are greatest allows scientists, conservationists and coastal communities to work together to develop effective sustainable solutions.

This is where Operation Wallacea plays a crucial role. Through long term biodiversity monitoring, OpWall expeditions help build a clearer picture of marine ecosystems around the world.

In Indonesia, OpWall’s marine research on Hoga Island in the Wakatobi Marine National Park has been tracking reef health and fish populations for decades. These reefs are among the most biodiverse on Earth, yet they are not immune to fishing pressure or the impacts of climate change, even within Marine Protected Areas. Long term datasets from places like this are invaluable, allowing scientists to identify trends that short term studies would otherwise miss.

OpWall’s work in South Africa’s Sodwana Bay similarly exposes volunteers to the complexity of reef ecosystems and the delicate balance between conservation and human use. Through reef ecology courses and underwater surveys, participants gain first hand insight into how fishing pressure, environmental change and biodiversity loss intersect.

Beyond these sites, marine research from Mexico and Honduras continues to add to baseline knowledge of fish populations and their ecological roles. This information is essential for protecting marine ecosystems into the future.

Photo by Dave Smith

A call to action

So what can we do, as individuals, in the face of such a global problem? Awareness is a powerful starting point. Choosing sustainably sourced seafood, checking for responsible fishing labels, supporting science led conservation and amplifying organisations that prioritise research and education all make a difference.

Even more impactful is getting involved directly, whether through citizen science, conservation initiatives or expeditions that contribute to long term monitoring and real-world research.

Overfishing is often described as an ocean crisis, but it is also a human one, driven by consumption, demand and our growing disconnection from the natural world. By rebuilding that connection and grounding our choices in science, there is still time to change course.

Final thoughts

Overfishing is one of the greatest environmental challenges of our time, but it is also an issue where collective action, from local fishers to global researchers, can make a real difference. Through research, education and on the ground action, organisations and researchers are able to empower people not just to witness the ocean’s wonders, but to protect them.

If we want oceans full of life for generations to come, the time to act is now.

Social Media Links