It is widely recognized that we are living in an era characterized by rapid biodiversity loss and rising extinction rates – the Anthropocene. The most recent IPBES report estimated that 1 million species globally are currently at risk of extinction. But who decides when a species is threatened, and how dire the threats it faces are compared to other imperiled species? And who decides when successful conservation work has reached a point where a species is no longer threatened? Or when a species is truly extinct? This is the work of the IUCN Red List – one of the most influential tools used by conservation biologists.

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) is one of the most important conservation organizations globally. While headquartered in Switzerland it is, as the name suggests, very much the hub of a union of conservationists, coordinating the work and expertise of thousands of other organizations and individuals around the world. While its work spans a wealth of subjects, it is perhaps best known for managing its most widely-used resource– the IUCN Red List.

The Red List is the authoritative source for determining the conservation status of species worldwide. Initially discussed as a concept by Sir Peter Scott (son of the famous Antarctic explorer and a distinguished 20th century conservationist), it was first published in 1966 and has been annually updated since it adopted its current format in the 1980s. As of 2026, it provides conservation assessments for >172,600 species, of which > 48,600 are considered threatened.

The Opwall sites support many threatened species, such as this Critically Endangered Coquerel’s Sifaka (Propithecus coquereli). The IUCN Red List is the authority that decides which species are globally threatened, and the threat level they possess.

Species assessments are not carried out directly by the IUCN themselves, but rather external partners with relevant taxonomic expertise. For example, all birds are assessed by BirdLife International, while cats or pigs are assessed, respectively, by members of the cat and pig Species Specialist Groups (SSGs).

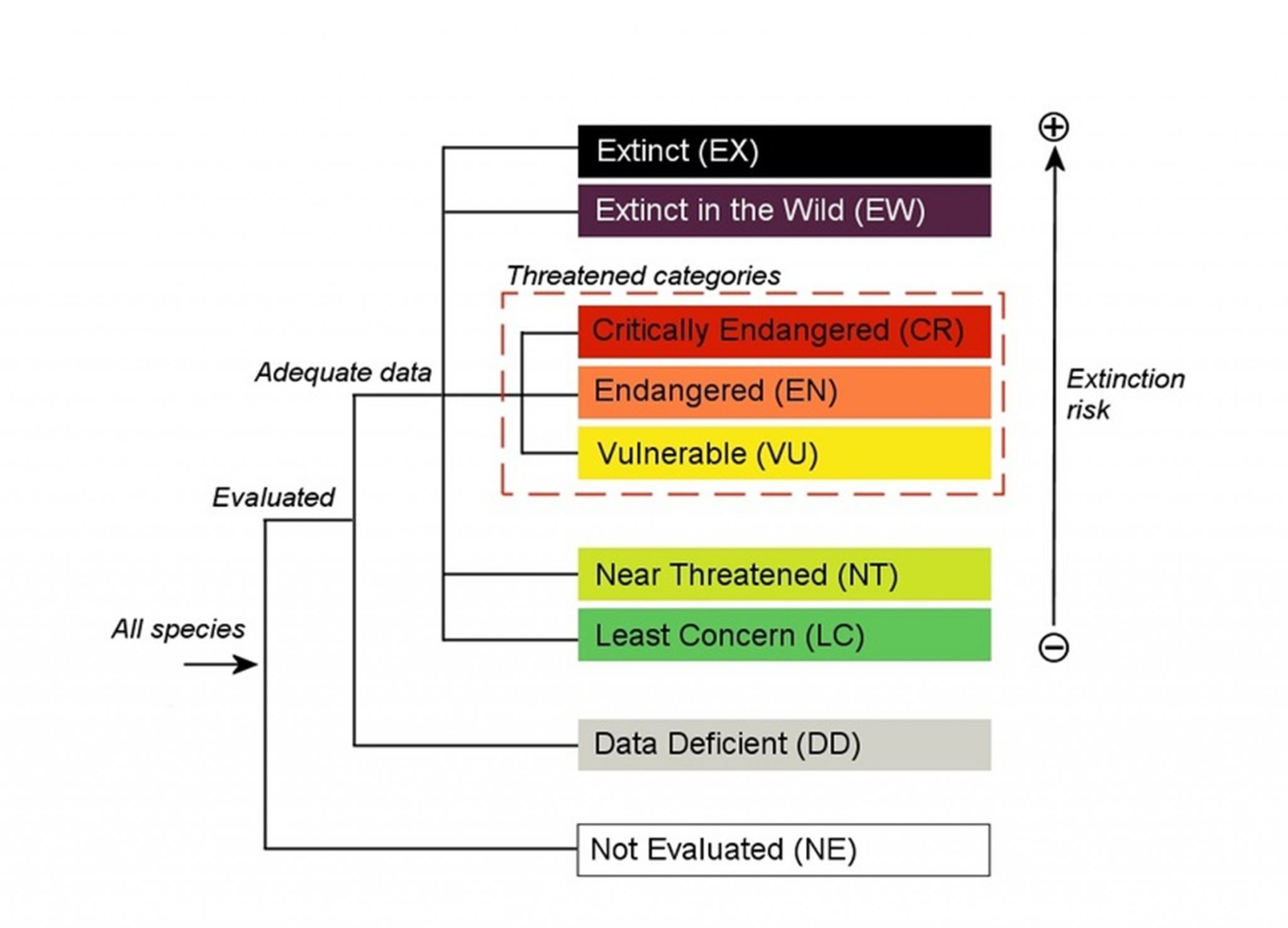

When making a decision on how to classify a species, these experts must consider available evidence relating to range size, population size and trends, and the extent of the threats they face, and assign one of eight categories. Each is governed by various quantitative criteria, but broadly they can be described (from the least conservation concern to the greatest) as:

Threat categories used by the IUCN, with Least Concern being the lowest threat category and Critically Endangered being the greatest (excluding Data-Deficient and Extinct species) (Source: IUCN 2025).

Once an assessment is complete, the information is passed on to the IUCN who curate the information on the Red List website. Typically, the IUCN completes a major update twice a year – once in spring and once in autumn. Once a species is added to the Redlist, it is then periodically re-assessed to check whether its conservation status has improved or deteriorated since the last assessment.

Fieldwork data is a key part of this assessment process, as without such data it is not possible to know where a given species occurs, where it has vanished from, and what its overall population trends are. Unfortunately, it has been documented that field-based conservation research is in decline globally, which can present a problem for IUCN assessments which rely on such data. As a fieldwork-driven organization, Operation Wallacea is often in a position to provide important information to help support researchers completing IUCN assessments. To date, our field data has contributed to 38 species assessments. Two recent examples from 2025 include, firstly, Van Dam’s Vanga (Xenopirostris damii) from our Madagascar site, which was downgraded from Endangered to Vulnerable, partly on the basis that our data from the Mariarano forest shows it has a larger spatial range than previously thought. Similarly, our documentation of the Blue-faced Rail (Gymnocrex rosenbergii) on Buton Island, Indonesia (where it was previously not thought to occur) contributed to the decision to change its Red List status from Vulnerable to Least Concern. Opwall data has also been used for the initial assessments of several species, such as Calamaria longirostris – a Critically Endangered species known only from a small area of forest in the south of Buton Island.

Van Dam’s Vanga (Xenopirostris damii) and the Blue-faced Rail (Gymnocrex rosenbergii). Two species that recently had their threat status reduced by the IUCN Red List, partly on the basis of field data generated by Opwall.

The real-world conservation value of the Red List comes from it providing conservation biologists with a frame of reference on where the most important priorities lie globally. This is often tied to conservation funding. For example, funding eligibility for the Mohamed Bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and the ZSL EDGE programme are both tied to a species IUCN threat status. The Red List also provides a means of tracking conservation success, as demonstrated when a species threat level is downgraded. A recent example of this is the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) which was recently downgraded from Endangered to Least Concern due to the success of conservation programmes designed to protect it. The concept of charting conservation success has also been developed further with the more recent IUCN Green List, more of which can be read about here. As well as providing threat categories, the Red List also provides a wealth of detailed information regarding the ecology and distribution of each imperilled species, the specific nature of the threats it faces, and current and recommended conservation actions – all vital data with respect to developing effective conservation strategies.

Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) recently had its threat status downgraded from Endangered to Least Concern due to the effectiveness of global conservation actions.

The IUCN Red List represents a colossal effort by the global conservation community, and since its early beginnings in the 1960s now supports >172,000 accounts which are periodically re-assessed, and with hundreds of new species being added each year. Much of this work is completed by scientists who offer their expertise on a completely voluntary basis. It should be noted that the Red List by no means represents an entirely comprehensive assessment of species on the planet (given that 2.15 million species have been described to date, and with overall global diversity estimated to be in the region of 8 million species including undescribed species), and heavy taxonomic bias exists within it. For example, almost all known bird species have a Red List assessment, while only 1300 (0.9%) of the 150,000 described species of fungi have been assessed. Taxonomic bias within the Red List has been formally examined by Opwall scientists and given a name – the Scottian shortfall (after Sir Peter Scott – the original inspiration behind the Red List) – more of which can be read about here. Red List assessments should also be used with care and in the right context. For example, even if a species is not threatened globally, that does not necessarily mean it is not highly imperilled and an important conservation priority on a more local scale – for example the case of the Wild Cat (Felis silvestris) in the UK. These shortcomings notwithstanding, the Red List represents an incredibly data-rich resource that becomes stronger year-on-year, and represents the most authoritative means of prioritizing species-level conservation efforts and tracking conservation success globally.

Social Media Links