It sounds a bit too good to be true to say that you get to spend your summers hunting for new species in one of the worlds most unique habitats, but that’s exactly what Dr Brogan Pett is doing with spiders in Madagascar. In this edition of Science Spotlight, we’re not going to be focusing on a single paper, but on one of our fantastic academic partnership between OpWall, Brogan and the SpiDivERse working group. We’ll talk a bit about SpiDivERse and the project in Madagascar and discuss how important taxonomy is as a field but also as a tool for conservation.

Brogan first joined us on site in Madagascar in 2017 after completing his master’s degree, already a keen entomologist and looking for a way into arachnology. It was there that he connected with Merlijn Jocqué from BINCO, joining forces with the team to collect samples and immerse himself in the world of spiders.

His first season really was a stepping stone and after returning home, Brogan was invited to Belgium to do some work at the Royal Museum for Central Africa with Rudy Jocqué, building expertise in spider taxonomy. Then in 2018, he was back in Madagascar working on BINCO’s first spider paper from Mariarano which focused on the ghost spider, a critically endangered species which at the time was known only from a tiny two-hectare patch of white sand. Its habitat is incredibly unstable, only being found adjacent to lakes in the dry forest means that any small deviations in microclimate could completely wipe it out.

Since then, Brogan has moved across the globe, living in Paraguay for a number of years before returning to the UK to complete his PhD at the University of Exeter and he is now based at the University of Iceland in Reykjavík where his main role involves researching spider biogeography across central Africa and the Indian Ocean. In 2023, he returned to the Opwall site in Madagascar with SpiDivERse to set up a systematic spider inventory, establishing the first large-scale project of its kind in the region.

SpiDivERse, meaning Spider Diversity and Evolutionary Research is one of the taxa specific working groups within BINCO (Biodiversity Inventory for Conservation), an organisation that aims to fill some of the growing gaps in biodiversity research, particularly for smaller and often overlooked groups of organisms. One of the biggest challenges facing taxonomy at the moment is that it is a declining field. Even some of the biggest museums are losing taxonomic staff left right and centre and hiring freezes mean that when people retire they are not replaced. This can result in major institutions going from a solid team of 20, down to 3 or 4 incredibly overworked people.

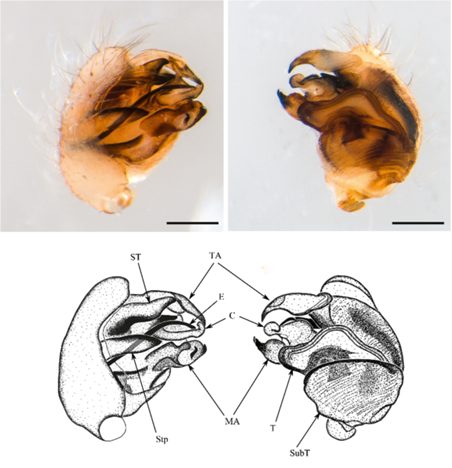

Description images for Larinia mariaranoensis sp. nov. Sourced from Escobar-Toledo & Pett (2024).

Part of the issue is that taxonomy doesn’t have the impact factor that is often required in modern academia. Too many fields prioritise fast-moving research and publishing heaps of papers that very quickly become outdated but will receive hundreds of citations in that time and are therefore treated as a great success. That is unlikely to happen for a really good taxonomic paper, but it shouldn’t matter because taxonomy is geared to be eternal. A species which has been well illustrated and diagnosed, can remain relevant for decades or even centuries. BINCO works to support early-career researchers like Brogan by providing training, access to museum collections, and opportunities to work with global experts. This support has been key in allowing projects like SpiDivERse in Mariarano to develop.

The scale of spider diversity in the Mariarano forests is an excellent case-study to show just how important museum science and taxonomy area. Within an area of roughly 10 km², Brogan and the SpiDivERse team have recorded around 220 spider morphospecies. Of these, at least 50 are definitely new to species to science, but that number could be as high as 70 or 80. This is an almost ridiculous level of hyper diversity and extreme micro-endemism just in one small corner of Madagascar and we are only just scratching the surface. So we need more taxonomists to travel to these places and catalogue new species. Without them, we would never have a situation like what SpiDivERse were able to achieve with the Wolf spider where they were given money to study the species and survey a number of other sites in the region to establish if it was found in other areas.

Photo by Jalal Khan

Documenting diversity is essential. Spiders sit at the top of the arthropod food chain, and arthropods make up the vast majority of terrestrial animal biomass. At the same time, rates of habitat loss and land-use change are extremely high. Without taxonomic work, there is a real risk that species could go extinct before they are ever described. Entire evolutionary lineages which have taken millions of years to evolve could be wiped out in a day. The Mariarano project represents the first large-scale, systematic study of spiders in Madagascar and provides a baseline for understanding any number of interesting questions

Taxonomy also has clear conservation value. In order to discuss questions such as; where else is this species found? How localised is it? How does it interact with other organisms? We need to be talking about the same thing and in most cases that means a described species with a recognised name. SpiDivERse has previously used data from projects in Cambodia to help inform increased protection for areas supporting critically endangered species. In Mariarano, knowing which species are present and how restricted they are allows researchers to start asking conservation-relevant questions: are species found in multiple forest patches, how sensitive are they to habitat change, and which areas are most important to protect?

A key part of Brogan’s work is training and involving students. Wherever he is based, he advertises opportunities for interns and volunteers to learn spider identification and taxonomy. Once they have learned these skills the have worked through real tropical samples from the field. At the moment, there are four student-led papers from the University of Exeter in review, and two former Opwall research assistants have been sent microscopes and samples so they can continue working independently to identify new species of spider.

Evarcha tsipikafotsy sp. nov. in vivo images, male. Photo credits: J.E.T. Sourced from Murray et al. (2024).

SpiDivERse also places a strong emphasis on local engagement. Many of the new species described are named using local languages or references to regional culture. This is a really important aspect of the project because as international conservationists we have to acknowledge the role that local communities play in protecting their home and bring the attention back to them. Further to that, it highlights to local people just how globally important their environment is and can hopefully convince them to help preserve it. A past project in the Congo described a number of new spider species which were named after local Bantu gods. Brogan then discovered that the publication was trending on LinkedIn and had thousands of shares from Congalese people who were so excited by the discovery because it was their own culture. Included in the recent discoveries are; Larinia mariaranoenisis which is named after the mariarano area; Larinia foko is named for the Malagasy word for spider and Thyene volombavatanany which means moustache (volombava) arm (tanany) in Malagasy, referencing the hairs on the underside of the legs. In Madagascar, this approach has encouraged MSc students to get involved in taxonomic research, and Brogan is now supervising projects with Malagasy students, helping to build local research capacity.

Photo by James Coates

The systematic spider project in Mariarano will continue until at least 2028, but Brogan’s broader research interests extend across Madagascar and the central band of western Africa. His work interests are on spider biogeography and how species distributions are shaped by land-use change, habitat fragmentation, and human development. Ultimately, his work will focus on where the group can have the most impact, where resources are currently lacking and conservation efforts are most urgently needed.

If you’re interested in seeing this work first-hand and possibly even working with Brogan then you should thinking about joining us as a research assistant in Madagascar this summer. Find out more about all of our expeditions by checking out the website or coming along to a webinar.

Title photo of Dr Brogan Pett, taken by Jalal Khan

Social Media Links